Why and when should teachers embellish a parable?

Learning intensifies when students engage in deeper analysis of a bible story. That is because the struggle involved in this teaching method inspires them to “own” the message of the parable. Studies show that it is the mind’s struggle to understand and create that is the learning process. Struggling causes emotions that change the brain chemistry. It excites the brain of the person who is struggling, which makes it more accepting of ideas and concepts.

Demonstration Lesson: How To Embellish A Parable

This teacher training lesson plan can be adapted for classroom use.

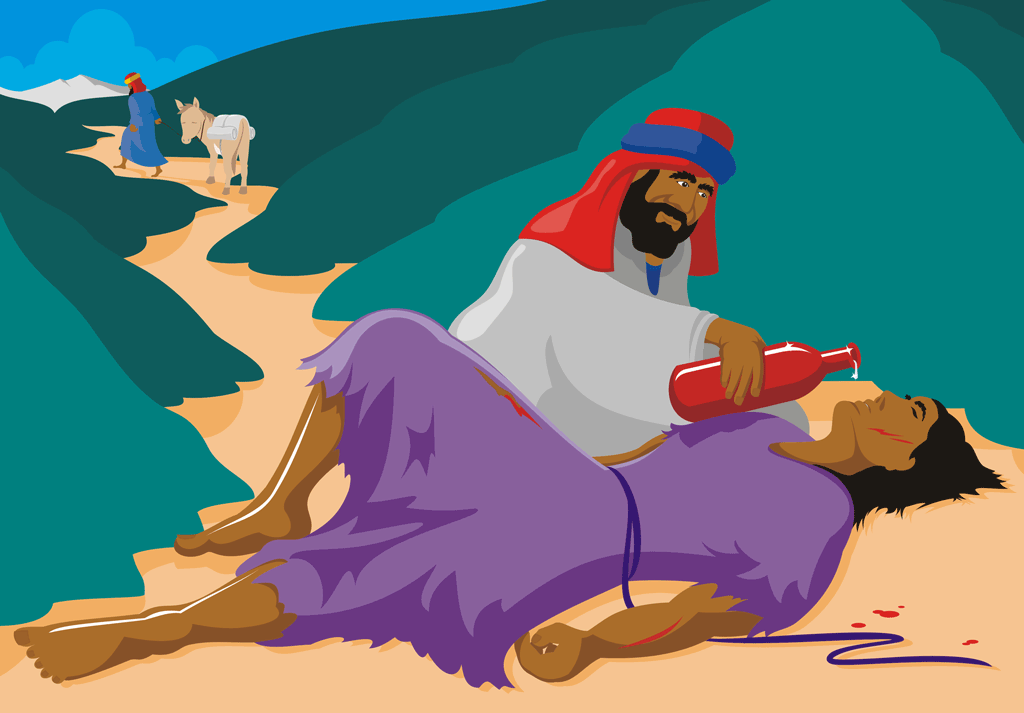

Embellishing a parable is a teaching method that helps religion teachers make bible times come alive. Let’s see how we can involve our students through embellishing the parable of The Good Samaritan. This demonstration lesson will provide a model for you to follow when applying this teaching method to other bible stories.

First, present the text. Students should have bibles. Tell them that we will read the story of The Good Samaritan. Then, we will develop the characters and create a new ending. To begin, it is necessary to imagine ourselves into the day Jesus told the parable. We want to understand the event so well that our embellishments remain true to Jesus’ message.

1 Become a storyteller.

Let’s time-travel to ancient Palestine. You are part of a group of 20 or so people gathered around the well of a small village near Nazareth. It is early evening.

You have worked all day in the vineyard in the hot sun. It feels good to relax and listen to a traveling rabbi.

Jesus has just finished preaching a sermon about the wonders of everlasting life. A lawyer in the audience is captivated by the possibility and asks, “Teacher, what must I do to inherit everlasting life?”

2 Ask students to read Luke 10:25-28 aloud. 3 Now, embellish the parable.

3 Now, embellish the parable.

Dramatize the lawyer’s state of mind. Use expression. Make yourself interesting to watch and to listen to. Tell or read the following.

The lawyer is not satisfied. He is overwhelmed by numerous questions swirling through his brain.

He wonders, “What does the Law mean by love your neighbor? Surely, a person can’t be expected to love everybody! And, where should he draw the line?”

In his mind he is reviewing all the groups of people he knows, wondering which ones he is required to love. He decides he should love his family and relatives, but wonders about the others.

What about Jews in another tribe or another country? Are they my neighbors? Some are pretty nice, but I don’t know them?

A Confused Lawyer

- How do I love people I don’t know?

- What about the outcasts, and all those unclean people who hang around the village gate?

- What about the gentiles?

- What about my enemies, like the Samaritans?¹

You may want to stop the story and ask your students to advise him, or you may wish to read his questions without comment.

The lawyer pursued Jesus with another, very powerful question:

- “Who is my neighbor?”

Jesus replied with the parable of The Good Samaritan,¹ and led the lawyer into answering his own question.

4 Ask students to read Luke 10:29-37 aloud.The Good Samaritan parable ends when the lawyer says the good neighbor is the one who treats all others with compassion (mercy and kindness), and Jesus says, “Go and do likewise.”

5 Now, create a sequel to The Good Samaritan.Of all the teaching methods for religion teachers, embellishing a parable is one of the most difficult to do well, because it calls for both creativity and a good understanding of the historical context of the text. This continuation to the parable of The Good Samaritan addresses a feature in the story that is seldom discussed:

- How did the lawyer feel when Jesus made a Samaritan the hero of His story?

The Jews loathed the Samaritans. Worse yet, a band of Samaritan terrorists had recently vandalized the Temple in Jerusalem, so tempers were running high. To answer the lawyer’s questions, let’s follow the priest, the Levite and the good Samaritan.

6 Distribute copies of The Meeting At The Inn to all. Ask your students to take turns reading aloud.Embellish A Parable: The Meeting At The Inn

Print The Story (PDF)

Download

It is one week later. The priest, the Levite and the Good Samaritan are on their return journey. By chance, all are staying at the same inn and sharing a meal together at the same table. Usually the Jews and Samaritans did not speak with each other, but sometimes things are different when people travel.

The innkeeper approaches and tells the Good Samaritan the injured man recovered and left after a few days. Now, the Samaritan owes more money for his care. While the priest and Levite watch with surprise, the Samaritan pays the injured man’s bill.

“I saw that man,” said the Levite, “but I could not stop. I had an appointment with a scribe in Jericho.”

“I saw him, too,” declared the priest. “He was lying beside the road, terribly bruised. Poor fellow! I thought about stopping to help him, but I was hurrying to Jericho to lead a worship service. I am so relieved you had the time to stop and help him.”

The Good Samaritan looked at them and threw up his hands. “Time! Time! Who has time? I was on my way to my son’s wedding. I arrived so late my family is still not speaking to me!”

The Levite was shocked. “How could you allow the troubles of a stranger to make you late for your son’s wedding?”

“That’s what my wife asked me. She thinks I am a fool! I still do not know who he was. I tried to pass by. But, when I heard him moan, I knew if I failed to help him that moan would haunt me for the rest of my life. What do you say? Am I a fool?”

The priest and Levite were so stunned by the question that they were silent.

The Good Samaritan finished his meal and left the table. The priest and Levite exchanged shocked looks.

“What a strange fellow,” remarked the Levite. “I don’t blame his family for being angry. He’s a fool. A stupid guy, just like all the rest of the Samaritans.”

The priest looked down. “Maybe not” he mumbled. “Maybe not. That man showed compassion. We did not.”

Discussion Questions

Select the questions that are best for your age group. Please see my commentary The Power of Questions.

Questions are an important teaching method for religion teachers because the struggle for answers continues the embellishment of the parable of The Good Samaritan.

1. Questions To Gain KNOWLEDGE

Through this parable Jesus taught us about the need for compassion. What is compassion? (Response to the suffering of others that motivates a desire to help, even if you must go out of your way.)

Can you describe a recent act of compassion done by a friend, a parent, a neighbor or by you?

2. Questions For UNDERSTANDING

What is the basic teaching of this parable? (Everyone is our neighbor and compassion is the ideal response to any person in need.) Ask students to give some examples.

Nepal is a small country on the other side of our planet. In 2015 it suffered a terrible earthquake. Many people died and many more were wounded. How can you show compassion to people so far away? (The United States government sent search and rescue teams and gave $10 million dollars to the charities that were sending teams to Nepal that would provide food, shelter and clothing for thousands of homeless people. Some were: Some American charities were: the Red Cross, Catholic Relief Services, Lutheran World Relief and the Samaritan’s Purse. Israel built a fully equipped field hospital with 45 doctors. During the next 18 days their team treated 1600 patients, performed 90 life-saving operations and delivered 8 babies).

3. Questions For ANALYSIS

Which character in the story did you like the best? The least? Explain.

Do you agree with the Levite? Was the Good Samaritan foolish to create anger in his family on his son’s wedding day?

Was the Samaritan a Good Samaritan to the priest and Levite?

(He role-modeled the ideal reaction to the wounded man.)

Explain why Jesus cast the Good Samaritan as the hero. (Perhaps He was trying to change their deplorable view of the Samaritans.)

What acts of compassion can individual people perform in their daily lives? The bible gives us a list of the Spiritual And Corporal Works Of Mercy.³ Some are taken from Matthew 25.

Feed the hungry.

Give drink to the thirsty.

Harbor the homeless.

Visit the sick.

Bury the dead.

Instruct the ignorant.

Counsel the doubtful.

Admonish sinners.

Bear wrongs patiently.

Forgive offences willingly.

Comfort the afflicted.

Pray for the living and the dead.

Be sure to learn how your church or synagogue addresses the Stranger Danger issue. It most likely provides regularly updated guidance on safe ways for young people to be helpful.

4. Questions For APPLICATION

What can we do to help a classmate who is being bullied, ridiculed or lied about? What if our help would cause the bullies to bully us? If we fail to find a way to help a person in need, is that a sin?

(Not all persons in need are in physical danger. Offer to tutor a student who is failing in a subject you do well. List other ways to identify and help classmates, parents, neighbors.)

Commentary

As we embellish the parable, we use the Samaritan to show humility.³ But, he isn’t all that sure of himself. So he simply describes his feelings. Being a humble man, he asks the priest and the Levite for their opinion of his actions. Because he asks for another point of view, the Good Samaritan’s attitude holds no trace of criticism for the others’ failure to help. In short, the Good Samaritan’s gentle words and manners invite the priest and the Levite to reconsider their own actions.

Footnotes to Embellish A Parable:

¹ Samaritans were people who lived in an area of Palestine called Samaria. They were descendants of Jews who had been sold into slavery hundreds of years earlier. Some of them escaped over the years and trickled back to the Holy Land and established their own community. They were Jewish, but their ways of worshiping had become distorted. The distortions offended the traditional Jews.

² Spiritual And Corporeal Works Of Mercy, From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

³ Humility (poor in spirit) is the willingness to receive from others. It is listening with respect to the point of view of others and considering it. It is a dialog, not a monolog.

Sources of Information:

For a discussion of compassion, search compassion.

The Gospel of Luke, William Barclay, Westminster Press

Why is it significant that it was a Samaritan who helped the Jewish man? What characteristics of a good neighbor did the Samaritan have? How does this story help us understand who our neighbor is? How can we become better neighbors?